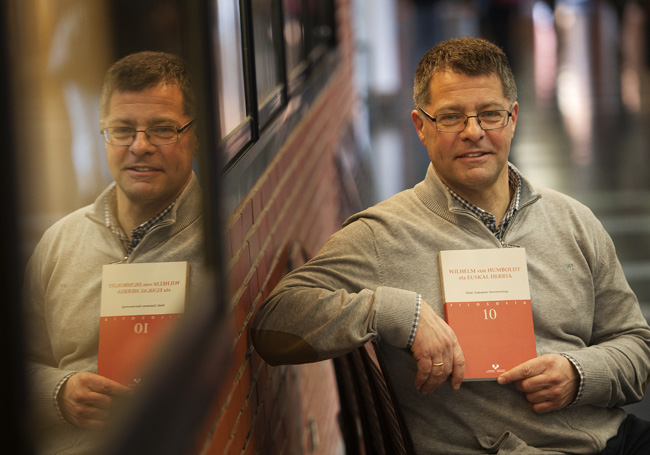

Iñaki Zabaleta-Gorrotxategi lectures in the Department of Philosophy at the UPV/EHU-University of the Basque Country. He received his PhD at the University of Cologne in 1998 with the defence, in German, of his thesis in Philosophy and based on the essays written by and research conducted by Wilhelm von Humboldt on the Basque nation and its language. He has now published a Basque adaptation of that thesis, but beyond the merely academic work he seeks to answer questions relating to what the Basque nation is or what can be referred to as the Basque nation.

-

In memoriam: Arturo Muga

-

Violeta Pérez Manzano: «Nire ahotsa ijito bakar batengana iristen bada eta horrek inspiratzen badu, helburua bete dut»

-

In memoriam: German Gazteluiturri Fernández

-

Azukrea eta edulkoratzaileak. Zer jakin behar dut?

-

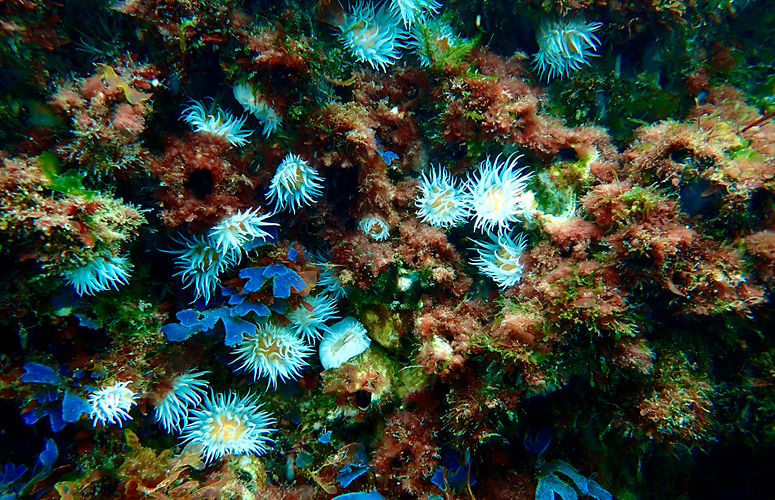

Itsasoaren gainazalaren tenperatura-igoerak aldaketa sakonak eragin ditu makroalgen komunitateetan

Iñaki Zabaleta-Gorrotxategi, lecturer in the UPV/EHU’s Department of Philosophy

«The identity of human beings and nations is developed together with the language»

- Interview

First publication date: 12/02/2018

Iñaki Zabaleta-Gorrotxategi’s latest book, Wilhelm von Humboldt eta Euskal Herria [Wilhelm von Humboldt and the Basque Country], was presented in Vitoria-Gasteiz. It systematically deals with the Basque studies undertaken by Humboldt over a twenty-year period in the early 19th century and sets them against the background of Humboldt’s general thought.

Who was Humboldt? Why did he come to the Basque Country and why did he choose Basque and the Basque Country as the subject of his research?

He was a thinker, an anthropologist, philosopher and humanist. His main concern was to explore what the human being is and how he/she might develop. In that respect, he found fault with the radical, learned approaches at the time and felt the human being needed to be examined in his/her historicity, his/her specific, diverse reality.

But human beings are not isolated islands, rather they live and develop with reference to a group. And that explains why Humboldt focussed his attention on different countries or nations. So, just as in the case of individual human beings, he felt it was necessary to get to know the nations directly and compare them with each other. He was convinced that it was the only way that a truly humanising anthropology could be developed. And that is why he became interested in the Basques, among other things.

What makes Humboldt’s work important?

He presented an open image of the human being as having the potential to advance in a development process, rather than as something that is closed or finished. What is more, he saw that process as both individual and collective.

After his stay in the Basque Country, in particular, he also felt that language exerted an essential influence on the nature of the human being. In Humboldt’s view the human being is human thanks to language, and he/she develops his/her identity together with the language. However, the language is only real among languages, and it must always be understood together with its social, historical and cultural aspects taken as a whole. Both society and the nation develop their identity together with the language.

What is more, it’s important to bear in mind the period in which Humboldt was thinking about all these things: after the French Revolution. From that period onwards, nations were becoming increasingly identified with their states; the concept of nation was becoming politicised and its cultural basis hidden. And in that context Humboldt reminds us that it is something dating back to before that time: the politics that comes afterwards cannot decide what a nation is and what it is not. That is why he ascribes a kind of natural nature to the nation. So he puts the research carried out on the Basques within a natural history of the human being.

How did the research he conducted in the Basque Country influence his Weltanschauung?

I would mention two aspects. The first is about the language: when he came to the Basque Country he found that Basque was a popular language surviving in the speech of citizens, and that provided him with a clue to understanding that the basic function of language was not of a literary, academic or scientific nature but anthropological. Language is what makes humans human, whether or not it is written down. That was, somehow, what he saw in the Basque Country and understood in general. On the basis of that it provided his anthropology with a new orientation: a linguistic orientation. From then onwards, he set out to examine human beings by exploring their language.

The second comes within the sphere of politics: Humboldt was also a politician and, among other things, was responsible for setting up the University of Berlin and implementing far-reaching reform of the education system in Prussia. In the end, he recognised that politics fulfilled a major humanising function: his task was to establish the conditions to enable citizens to freely develop their identities. So in view of all that, it therefore comes as no surprise that he devoted his attention to local politics when he came to the Basque Country. And he saw something that struck him as strange: self-governance or the direct participation of citizens, for example, in the fact that each municipality used to send its representatives to the General Assemblies.

It is true that Humboldt describes this largely according to what he had been told; but there is no denying that he was a highly experienced person: he was intimately familiar with the situation of Berlin, he had lived in Paris during that period, he had recently been to Madrid and when drawing a comparison he came across an unusual way of engaging in politics in the Basque Country. Specifically, he spoke about a popular enlightenment that was simultaneously far removed from despotism and which needed no revolution.

Why did you choose Humboldt as the subject of your research?

Largely out of a personal concern and also out of a social commitment: when you read the newspapers, listen to the radio, and watch TV, the subject of nation emerges as a controversial issue over and over again (today you only have to take a look at Catalonia). And that alone shows how important it is to reflect on the concept of nation and to take its history into consideration.

So with that in mind I wanted to explore how we can understand, in a normal way, what we call nation. And then, when talking to various people, and I am deeply grateful to Joxe Azurmendi in particular, I heard about how Humboldt came to the Basque Country and made interesting reflections on the interaction between nation and language.

On occasions I have been asked whether Humboldt was a nationalist. I don’t know whether he was or not, but he was a nation lover.

Humboldt certainly reflected on the nation and what he said at the start of the 19th century has not become outdated.

No, it hasn’t, and it cannot become outdated, because what he said was something basic. Humboldt saw the nation in conjunction with the language; in his view, the nation was a speech community. There’s nothing new about that, it is eternal and cannot end up obsolete. Whenever we look at history, we in fact do so because we want to understand ourselves better.

At the end of the day, what Humboldt was asking was this: What makes a group a group, what holds the members of that group together, what keeps people together around an identity? And after examining various aspects (in the Basque Country, for example, he took the physiognomy, popular culture and politics into consideration), he reached a single conclusion: more than all those things it is language that binds the group members to each other.

In relation to that, he also said that if the language were to disappear, then the nation would also be lost. And the truth is that he was quite pessimistic about the Basque Country: he saw it on the verge of disappearing, largely because the nation governance that politicians tended to undertake lacked an anthropological basis and was not humanistically orientated. The French Revolution had already put an end to the ancient customs of the people in the Continental [French] Basque Country, and he saw great enthusiasm for centralism in the Madrid government.

Humboldt conducted research into and wrote about Basque in German; you wrote up your thesis in German about what had been written about Basque in German and, finally, as a way of coming full circle, you have produced a Basque version of it.

That’s right. The initial aim of the thesis was to understand Humboldt’s philosophical anthropology and, within that, to specify how the Basque issue influenced all this. Yet today, despite the fact that the subject explored is the same, the opposite perspective emerges; in this case, the aim is, with Humboldt’s help, to understand the Basque issue better.

One example. Humboldt’s visit to the Basque Country opened his eyes to understanding the intrinsic anthropological dimension of language: in language matters the practice is more important than the result, and that was the guideline he followed to direct his subsequent linguistic research. And today that is precisely where the biggest problem in the normalisation of Basque is to be found: the most difficult and most important thing is not to compile dictionaries or grammars but, more than anything else, to integrate the use of the language into our daily lives.

The book is also a way of settling a debt; indeed, Humboldt learnt much more about the Basques than what we Basques have learnt about Humboldt. It is often said that he was the friend of the Basques, but that is about it. Occasional studies have certainly been made of his texts on Basque grammar or on “Vasco-Iberismo” [hypothesis that Basque could be directly related to an ancient Iberian language] and there have been various translations into Spanish about his travels. But until now no general study has been made of Humboldt’s Basque works.

In the book it isn’t easy to see the dividing line between the two of you: where Humboldt ends and where Zabaleta begins. Has he left any impression on you?

Of course he has! The questions I myself raised at the beginning have somehow found their answers in him. I think Humboldt correctly understood the Basques within their identity.

Humboldt has shown me how to speak about nation in normal, comprehensible terms, in general and in the Basque case, far from essentialisms and without being embarrassed. I agree with Humboldt on what he says about that.

You would have had some very deep discussions if you had been at his side.

No doubt about that. I would have liked to know how he saw the Basque Country today and in the future.