Even though we have been told the contrary, women also used to perform certain dances, such as the “aurresku”, which were subsequently regarded as male dances. In this respect, a piece of research by the UPV/EHU’s Department of Audiovisual Communication and Advertising has explored when and how gender identities and stereotyped roles prevailing in Basque dances were built, and has confirmed that women danced throughout the ages in the history of Basque dance.

-

In memoriam: Arturo Muga

-

Violeta Pérez Manzano: «Nire ahotsa ijito bakar batengana iristen bada eta horrek inspiratzen badu, helburua bete dut»

-

In memoriam: German Gazteluiturri Fernández

-

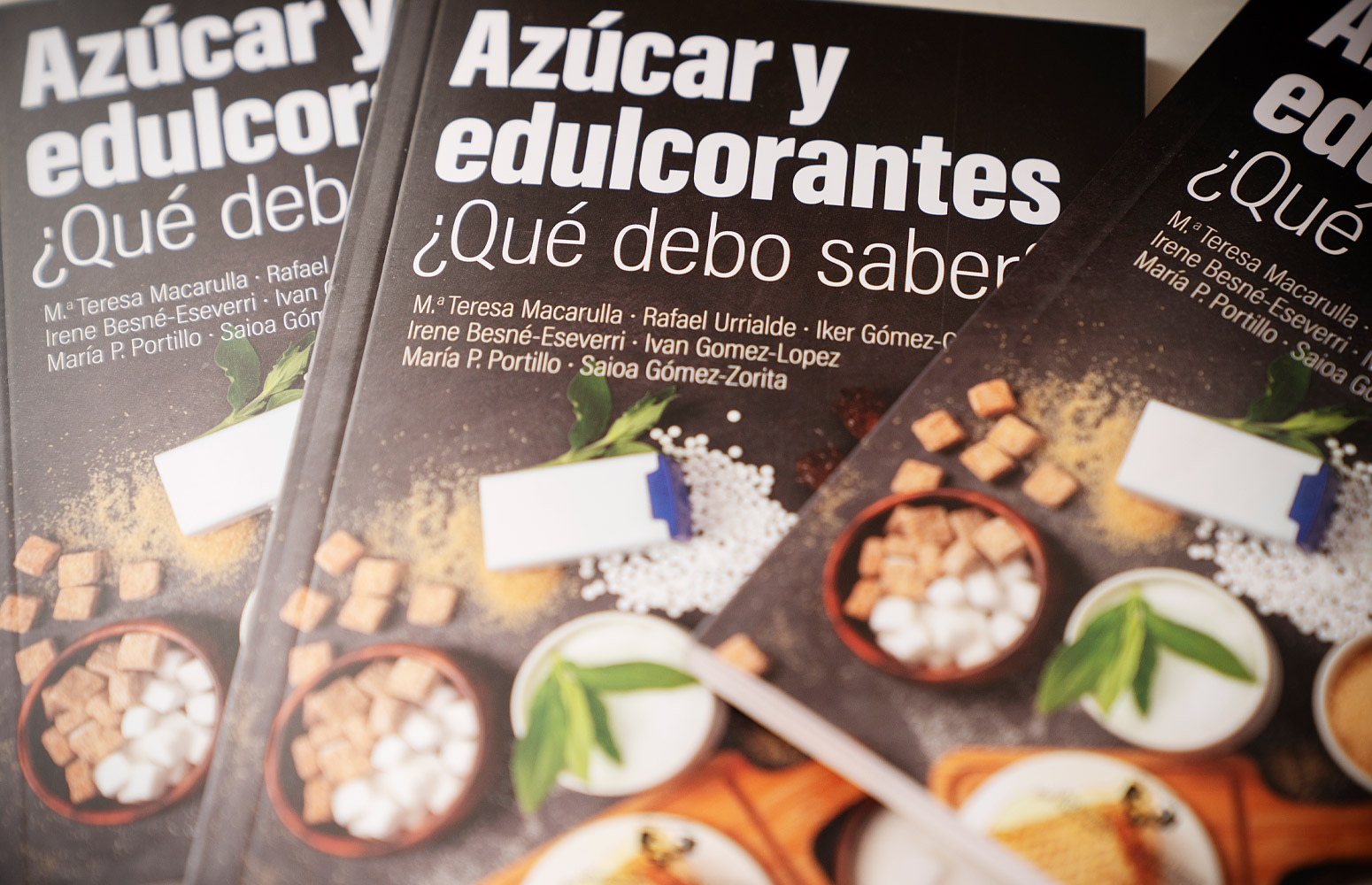

Azukrea eta edulkoratzaileak. Zer jakin behar dut?

-

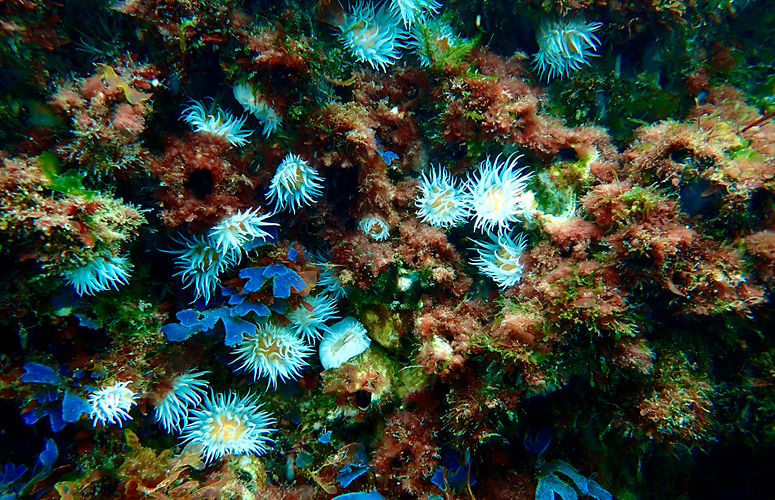

Itsasoaren gainazalaren tenperatura-igoerak aldaketa sakonak eragin ditu makroalgen komunitateetan

Women have always danced

A study by the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU) explores the origin of the binary stereotype that has prevailed to this day with respect to Basque dance

- Research

First publication date: 05/03/2021

Why do women’s dances and men’s dances differ? Is there a female dance and a male dance? Have the dance costumes worn by girls and those worn by boys always been different? “These concerns and similar questions have been emerging in recent years when it comes to reflecting on the performing of traditional Basque dances. This reflection on dance and gender is taking place in the 21st century, but the questions refer mainly to past facts and ideas which have played a role in building the present. Insofar as these dances are defined as traditional dances, I have sought the answers to these questions in the past,” explained Oier Araolaza-Arrieta, a UPV/EHU researcher and manager of Dantzan.com, an association set up to promote and disseminate dance.

“There is a mistaken view of traditional Basque dance and gender: people believe that women did not dance or at least did not perform important or spectacular dances. It is an idea that some researchers have refuted over the last twenty years, but it is very widespread and deeply rooted, and despite being inaccurate, remains very strong in dance companies and among the general public. The dances women performed were always regarded as new ones or creations to provide them with an opportunity, or they were regarded as having been adapted from the male repertoire,” said Araolaza.

In actual fact, “this work aims to refute that mistaken idea and that is why I have analysed various periods in traditional Basque dance: the last part of the 19th century and the first part of the 20th. And it is in that chronological framework that the transformations in gender perspectives and the building of a new tradition in Basque dance coincided”, said Araolaza-Arrieta.

“In the case of the aurresku [Basque dance of honour], we have seen that it has been systematically repeated since the 1920s that women did not dance it. However, that is not the case; we have known about cases of women dancing the aurresku until the 20th century. At the start of the 20th century separate repertoires were produced for dancing: dances for women and dances for men. Up until that point this classification did not exist, and the aurresku, for example, which used to be performed by both men and women, was categorized as a dance for men, and from then onwards it was performed by men. Something similar occurred with the ezpata-dantza [sword dance], makil-dantza [stick dance] and, to a certain extent, with the dances characterised by strength. By contrast, the much more tender, sweeter dances were classified as dances for women even though previously they also used to be performed by men (arku-dantzak [arch dances], zinta-dantzak [ribbon dances], sagar-dantzak [apple dances], etc.),” stressed Araolaza.

“In this work I explored why some experts at that time said that women did not dance the aurresku. It was not a conscious choice, but had to do with Christian morals, a story handed down when nationalism crossed paths with the gender perspective,” he stressed.

“On the other hand,” added the researcher, “the dress code also exerted an influence. Men had to wear white, long trousers, rope-soled footwear, hats and red sashes. Women were expected to wear a red skirt and a headscarf. Previously, it was very common for women to wear hats and they also performed in bloomers”.

This study “has not only confirmed that women had been dancing at all times throughout the history of Basque dance, it has also provided an opportunity for women’s contributions and influences to start to emerge and, despite the fact that this was refuted, it has allowed one to see that they participated in a major way and in a more important way than that reflected in the history of dance”, said Araolaza.

According to the researcher, “through this work I wanted to make the point that the gender roles manifested in Basque dance and made public through dance had been built, and that without the burden of them it is possible to act more freely. If we do that, I believe that by means of tradition, more honest than treachery, we will be acting more fairly with respect to all the members of our community and with respect to women especially. I don’t know whether dance has made us freer, but if dance is freer, it is bound to make us happier”.

At the same time, “in this piece of research there is a wish, an effort, an intention to bring the university closer to dance. Dance needs the university, I think it can benefit from this system of learning and transmission. And I believe that the university also needs dance. It is an area of learning integrated into the university dance system in other universities. Here, in our case, dance does not enjoy its own space”, stressed the dantzari [Basque dancer] and anthropologist Oier Araolaza-Arrieta.

Additional information

This research was carried out within the framework of the PhD thesis by Oier Araolaza-Arrieta (Elgoibar, Basque Country, 1972) entitled Genero-identitatea euskal dantza tradizionalaren eraikuntzan [Gender Identity in the Building of Traditional Basque Dance]. He conducted the research with a grant from the UPV/EHU’s Mikel Laboa Chair and participated in the PhD programme in Social Communication run by the Department of Audiovisual Communication and Advertising. The thesis was supervised by Leire Ituarte-Pérez, lecturer in Audiovisual Communication and Advertising at the UPV/EHU, and Nerea Aresti-Esteban, lecturer in Contemporary History at the UPV/EHU. The thesis was written up in collaboration with the Mikel Laboa Chair of the UPV/EHU and the Dantzan.com association.

![Aurresku [Basque dance of honour] in Orio, Basque Country, 1942 (Vicente Martin. Kutxateka)](/documents/10136/27612606/vicente-martin-kutxateka_dest.jpg/9c9b8ae5-eb96-bdde-1891-7e343daf22c1?t=1614933710481)