-

In memoriam: Arturo Muga

-

Violeta Pérez Manzano: «Nire ahotsa ijito bakar batengana iristen bada eta horrek inspiratzen badu, helburua bete dut»

-

In memoriam: German Gazteluiturri Fernández

-

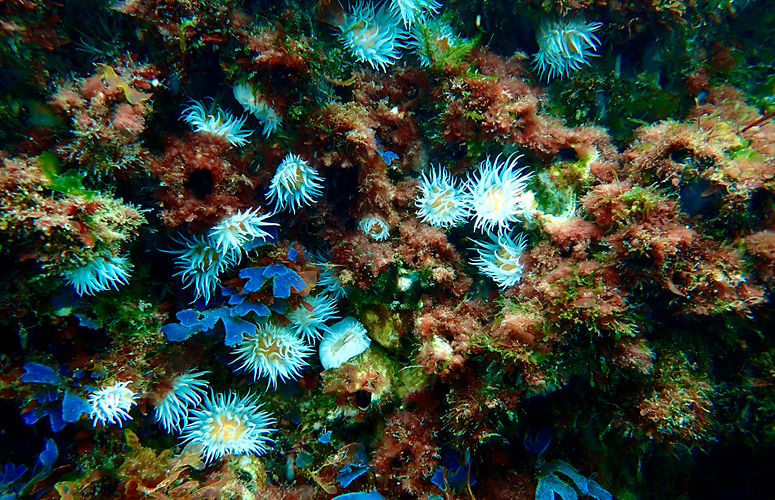

Itsasoaren gainazalaren tenperatura-igoerak aldaketa sakonak eragin ditu makroalgen komunitateetan

-

Azukrea eta edulkoratzaileak. Zer jakin behar dut?

Margaret Bullen

What can a social anthropologist do?

Sub-dean (Practicum). Faculty of Education, Philosophy and Anthropology. UPV/EHU

- Cathedra

Lehenengo argitaratze data: 2017/02/23

Artikulu hau jatorriz idatzitako hizkuntzan argitaratu da.

Espe makes her away across a field, feeling rather unsure about where her map is leading her, but at the same time she senses she is following in the footsteps of the man hailed as the founding father of Basque anthropology, Joxemiel Barandiaran. Today though she is following the instructions of the master of ethnography, Fermin Leizaola, who has sent her on a quest to identify the lime kilns dotted across the Gipuzkoan landscape and track down the men and women who stoked the fires which would produce the whitewash for the surrounding farmhouses. This is ethnography of the classical kind: identifying and documenting artifacts and work tools, recording stories of how people made and used these objects, and how the objects in turn brought sustenance and significance to their lives.

The figure of Aita Barandiaran has coloured the imaginary of what anthropology is in the Basque Country, painting a picture of men in cassocks, rummaging in caves and roaming the mountains in pursuit of skulls and myths. As I have discussed in the chapter Doing anthropology in public: Examples from the Basque Country in Sarah Pink and Simone Abram's book, Media, Anthropology and Public Engagement (2015), the general population of the Basque Country is familiar with and interested in what anthropologists have to say but their notion of what anthropologists do tends to be closer to the work of archaeologists, Indiana Jones style, and the physical anthropologists and forensic scientists of Bones or closer to home, Paco Etxeberria's Reader of Bones.

So what can a social anthropologist do? Espe's project is just one of many kinds undertaken by apprentices and practitioners of this discipline today. If we understand that anthropology is concerned with the study of diversity, with what makes one human group different from another, with how groups organize and interpret reality in particular ways, then we will begin to grasp the applicability of our discipline to a vast array of situations and occupations. That's what makes the Irish Independent able to affirm -in 2014- that anthropologist ranks as the second of fifty top jobs for the future. Sandwiched between the number one career in information technology project management and software systems developers and testers, it is surprising to see how highly anthropology is valued by experts of the job market. "The study of people can take you into almost any career path, anywhere in the world", declares Sarah Stack (Irish Independent, 24/06/2014).

Let's look at just some of those paths and see what anthropologists around us are up to: museum curation and cultural management; education, research and consultancy; government and social, cultural or linguistic policy making; business, marketing and design; social work and mediation; international and local development.

Social anthropology has a big concern in heritage, both material and immaterial, and this means many anthropologists work in museums and cultural centres where history and heritage are managed and displayed, or in institutions where cultural policies are drawn up and implemented. They might design exhibitions, devise material to enhance visitors' experience or to help children interact with the exhibits, or they might carry out studies of the public, their opinions and interpretations of the displays. Outside the confines of the museum walls, many anthropologists work alongside social historians to gather in and lay down for posterity a collective or "historical" memory: stories of people who have lived through wars, left their farms and homes for a job in the city, left their countries in search of a better life overseas.

We tend to think of culture in terms of 'high culture' -art, literature, theatre, music, dance, film- and anthropologists are engaged in all of these areas, evaluating Donostia's jazz festival, analyzing the 'bertsolari' championships, exploring resistance to change in local dance, making documentaries. But culture is much more than an art form. Culture as we understand it pertains to whole way of life and so cannot be contained in a glass box or placed neatly on a museum shelf, it spills over, it's messy, ever changing, ever defying our definitions. Hence culture is at the core of anthropological enquiry, the mesh of much of our research carried out not only in the university, but also in consultancies such as Farapi, founded by anthropologists and focused on anthropological research, or Aztiker, more sociological in its approach. Both employ qualitative research methods to capture the detail of social life, to bring social actors' experiences and opinions to bear on policy making or on production. Farapi, for example, has teamed up with a design group and developed unique strategies for identifying users' needs and preferences and incorporating them into new products.

Often people wrinkle their noses at the thought of anthropology being involved in the business world: business is a 'bad word', seemingly anathema to the desire for social justice and equality which arises from many anthropologists positioning themselves alongside the groups with which they work, and adopting a role of advocacy, in defense of human rights and in assertion of a particular cause. This is where we see anthropologists taking on roles as mediators, whether in conflict resolution or in intercultural communities. Nevertheless, although business and design anthropology remain fairly unknown in the Basque context, there are many interesting initiatives coordinated by the Applied Anthropology Network of the European Association of Social Anthropologists (EASA) which organizes an annual conference entitled Why the world needs anthropologists. As one of the members protested at a meeting in Milan last summer, business does not have to be branded 'bad': why should it be wrong, for example, to help understand the needs of people with functional diversity and communicate their preferences to the companies who supply them with different kinds of technical aids?

Many anthropologists work on different kinds of development projects, at home and abroad. It might be a water project in El Salvador, trying to detect the gender bias of the implementation of a new water supply and identify the needs of women (often overlooked in technological undertakings), a study of young people's use of mobile phones in Euskadi and Peru to detect and prevent abuse, or a photo project on child workers in a deprived area of Lima. Architecture and urban development are other areas where anthropologists are a crucial part of project teams, helping to explain local uses and practices and ensure that their perspective is taken into account. Anthropologists working in non-governmental organizations in the Basque Country might be giving administrative advice and support to migrants, running projects to facilitate integration, while others campaign against the abuses of multinational companies around the world. Another important line of activity in our context is language use, planning and policy.

So with such a diverse picture of what anthropologists can do, what do all these jobs have in common, what are the skills we have to offer? We have a way of approaching a problem from a holistic point of view, that is we like to get the full picture, take into account the context, the place, the time, the different actors and their take on the matter in hand. We develop the anthropologist's gaze, the ability to observe but not from afar, to get up close to those we wish to understand, to focus on the detail which surprises us and leads us to examine it further. This means we often work at a grassroots level, from the bottom up; we try to stand in other people's shoes and see things with their eyes. Our key is the capacity to take on board diversity, to detect the new, to learn from the contrasts of different ways of doing things; but it is also an attitude, an open-mindedness which, as Margaret Mead once said, was necessary to be able to "look and listen, record in astonishment and wonder that which one would not have been able to guess".

Photo: Nagore Iraola. UPV/EHU.