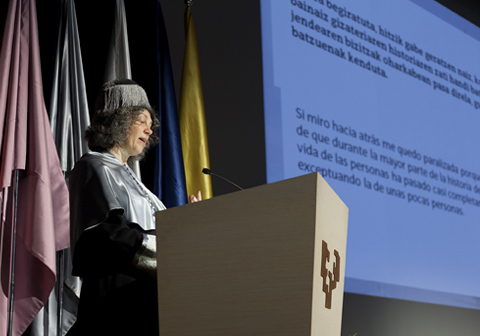

Sonia Livingstone is a professor of the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), and over the last 25 years has dedicated much of her research to children's relationship with the media and the internet. Some of the most prominent projects she has led are EU Kids Online, Net Children go Mobile and The Class. In 2014 she was awarded the title of Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) for services to children and their internet safety..

Sonia Livingstone, researcher and international expert in children's internet use

«There's a lot of myths about what children do on the internet and what it means for them»

First publication date: 16/06/2017

Sonia Livingstone has visited Bilbao recently to receive an honorary doctorate from the UPV/EHU-University of the Basque Country for her contribution to the research and dissemination of knowledge in connection with the use that children make of the new technologies. Her relationship with the UPV/EHU started in 1995 and continues today with the project EU Kids Online, a network in which research personnel from over 30 countries are participating in..

What would be the ideal scenario where children would enjoy secure use of the internet in terms of parents, kids, the school network?

Well, the ideal scenario. Everyone will know a bit more than they do now about what the benefits of the internet could be for children and they would be less anxious. There's a lot of myths about what children do on the internet and what it means for them and there's a lot of misunderstanding and not enough research.

So I would have a more informed public in schools, absolutely, teachers would have up-to-date training on the possibilities and risks of the internet; I would have a better guidance to parents, and we also really need more regulation from the State to the companies, because the companies are not transparent, and the internet changes so fast.

And now, coming to the real world, have you seen differences between boys and girls both in terms of the risk that threatens them and in terms of the perception of those risks?

Well, when we do our surveys there are often not such great gender differences. I think we always expect the differences in the behaviours but actually the boys and girls especially in adolescence they are in the same community, it's a mixed environment, so what happens to one happens to the others.

The gender differences are often fairly small, except that girls say what happens on the internet. So they are more upset by what they see. There are some other differences, I think, in boys seeing sexual images more, girls having more encounters with online strangers, but they're not huge.

«We want the opportunities for everybody, but sometimes we overprotect because of the risks»

So the question in my mind is often with the boys, they say they're are fine, so does that mean they are fine? I think we should still worry about boys either because they are vulnerable and very often they don't express it and/or because they feel pressured into taking the aggressive position.

And what about the differences among countries? I mean does the social network or application that is used most influence in any way the risk or problems that emerge in each country?

We should probably say that the differences within any country are usually bigger than the differences between countries. But the countries where we see more risk are more in the Eastern European countries. And sometimes it's the particular social network they use but it's also the amount of government pressure on those social networks. So even if they all use Facebook, Facebook in Britain is a safer place than Facebook in Bulgaria; when States put more pressure on the companies, they become more concerned about their social responsibility.

And the other thing that matters is how much attention there is in the school and how much awareness there is among the parents. And, again, the State has the responsibility for all of this: they set the curriculum, they pay for the campaign that brings attention to the parents, and they put the pressure on the companies.

An absolutely widespread problem is the addiction of children to their mobile phones. How could this problem be managed?

I don't quite accept the definition of the problem. Addicted to them? The practices have changed. We've created a world in which everything is connected to the phone, so of course they always have it with them and they always look at it. So then it has an appeal and it becomes a habit, and perhaps it becomes a bad habit, and perhaps it becomes a rude habit, but they're not drug addicts, they're not alcoholics, they're not even gamblers. So I just would like us to be really careful about criticising them, embracing the world we made for them.

Is it difficult to find the balance between opportunities and risks young people have from their online lives?

I think the difficulty is that the majority of children grow up to be resilient, thoughtful, sensible people, and a few children are vulnerable and we don't know really how to tell which is which. So we worry about the risks because of the few and we have to worry, we want the opportunities for everybody, but sometimes we overprotect because of the risks. From the point of view of research and policy and practice, the weak point is not visible to us until it's too late, and that makes us all very anxious.

Let's turn to parents. First of all, at what age should children own a smartphone?

What we see in Britain I think is something quite healthy: the last two or three years we see a decline in the smartphone because the tablet is taking over and specially for young children. There's a kind of crossover, and the crossover in Britain is round about 12 years old. By that age they each need their own personal device, but before that they can share it at home; they can use the tablet together. It's a better tool for sharing and for playing together.

What advice should parents give to children for a positive online experience?

This is a key question. I think parents have no idea. I haven't interviewed parents who know which sites will help their children learn, or which sites will really support their children's creativity.

If you talk to the industry, they say yeah we make all these great sites. They call them all educational. Then the ones that have the most money reach the child, the most advertising, not the ones that are most creative for children.

And there is no librarian. You know the librarian used to say this will be a good book for your daughter. She's 7 and she likes dancing. No one does that on the internet.

And how should parents behave with children to ensure they feel they are protected but not limited by them?

Number one: parents should put their own phone in their pocket and they should look at their child and they should talk to their child in a sustained way, you know, without checking the phone. This is the most important thing. Then number 2, if they see anything that worries them, they should not say "Stop that, this is dangerous!". No. They should say: "That's interesting. What are you doing? Can I see? Can we talk about it?"

What needs should be taken into account by policy makers to fully develop the digital skills of children?

In one way I think the education for digital schools is primarily a challenge of education: we understand that reading, writing and mathematics take years to develop, and how you get more complex gradually. But we don't think of digital schools as an education in itself that takes such pedagogic thought and we don't integrate it with the other things that we teach. And I think another problem is that very often digital skills is something that is taught as an extra, it's not something the teachers had a lot of training in.

Finally, what do you think about the role of the media when they try to warn young people about harmful phenomena on the internet but are actually based on rumours, such as the Blue Whale?

In my experience people who work in the media are generally educated and critical, who are trained to ask tough questions about the validity and the evidence base of the problem. But they don't always do very well when it comes to children and the internet and I don't actually understand why. So the Blue Whale is perfect because it, I mean, one moment I particularly notice it when a tech expert media company also fell for it, they said children were committing suicide all over the world from this website. No evidence, no link to the site, no checking that this child who did commit suicide had played the game. I mean just a kind of basic journalism process. No talk of addiction!

Image gallery

-

Sonia Livingstone. Photo: Tere Ormazabal UPV/EHU -

Sonia Livingstone. Photo: Tere Ormazabal UPV/EHU -

Sonia Livingstone. Photo: Tere Ormazabal UPV/EHU -

Sonia Livingstone. Photo: Tere Ormazabal UPV/EHU -

Sonia Livingstone. Photo: Tere Ormazabal UPV/EHU -

Sonia Livingstone. Photo: Tere Ormazabal UPV/EHU -

Sonia Livingstone. Photo: Tere Ormazabal UPV/EHU -

Sonia Livingstone. Photo: Tere Ormazabal UPV/EHU -

Sonia Livingstone. Photo: Tere Ormazabal UPV/EHU